Angelo Pizzo (writer/producer)

David Anspaugh (director)

David Neidorf (Hickory Husker Everett)

Eric Gilliom (J. June)

Jane Anderson (costume designer)

Fred Murphy (cinematographer)

Bill Chestnut (Oolitic team member)

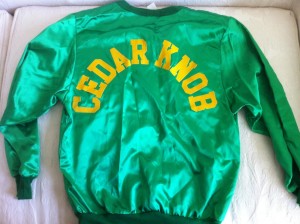

Todd Baxter (Cedar Knob team member)

Chelcie Ross (George Walker)

Spyridon “Strats” Stratigos (technical advisor and referee)

Brad Long (Hickory Husker Buddy)

Steve Hollar (Hickory Husker Rade)

Interview with writer/producer Angelo Pizzo

October 10, 2017

Hoosiers is often described as inspirational and uplifting. But you’ve noted that in many respects it’s a dark film about people in pain. One of the movie’s main themes, other than basketball, is redemption and second chances. Why is it important for a sports film to include weightier themes?

Because it has to be relatable to people outside the sport. If people are only drawn to a sports film because they appreciate that sport, or are rooting for a team, you’re counting on an audience that’s too small. And you’re counting on the audience to project the rooting interest into someone who just wears the uniform. They have to connect to the human dilemmas and human issues that your protagonists are struggling with. That’s the key to success for any film. You feel their pain, and you feel their happiness, their joy. If you connect with somebody through their vulnerabilities, insecurities, or blind spots, that connection is how you feel about yourself, oftentimes. When there is a dramatic success or victory, you feel enlarged; you feel hopeful.

Hoosiers isn’t really based on a true story. It’s inspired in part by the real-life 1954 Indiana basketball state-champion Milan Indians.

We tried to embrace the spirit, the circumstances, the situation. We never intended for the movie to be a docudrama. I just wanted to capture that time and that place—the possibility of something like that happening. I needed the freedom to pick and choose the dramatic arcs of all the characters.

Even though Hoosiers isn’t the Milan story, the 1954 Milan team and their fans have claimed the movie as their own. Their museum contains a fair amount of Hoosiers memorabilia.

I’m happy that they have embraced it. The thing that really mattered to us was, when we first screened it, [1954 Milan player] Bobby Plump was among the first people in Indiana to watch the movie. We were nervous, because we wanted to make sure we got it right, and they would tell us if we hadn’t got it right. After that screening, Bobby Plump, the guy I was worried about more than anybody, came up to both of us, put his arms around us, hugged us, and said, “You got it right. You nailed it. It’s not our story, but you captured the time and place.”

In the fourth quarter of the 1954 state-championship game, Bobby Plump stood there, unmoving, holding the ball (which was allowed back then) for long stretches of time. When the movie came out in 1986, one critic commented that having Jimmy Chitwood do the same thing might have been just as suspenseful as showing a lot of fast action throughout the game. Did you ever consider writing the final game to show Jimmy holding the ball?

Too boring. And it wasn’t confident basketball. I hate that strategy. I wouldn’t want to be in the stands watching it.

Some of the characters in Hoosiers were inspired by people you knew growing up. I really like Opal Fleener, Myra’s mom, the feisty, funny, older female basketball fan. Was she based on a real person?

When I did research on what farm life was like, my main go-to author who had written about day-to-day life on the farm was quite a wonderful author who lived not far outside of Bloomington. Her name was Rachel Peden. I culled a bunch of her quotes and inserted some of them into the script. I pictured someone who was fairly simple, salt of the earth, told it like it was. And her basic day-to-day existence is running a farm. That’s what all the characters do, and yet I never showed them doing it, except for Opal.

A look at the original screenplay reveals many supporting characters, subplots, lines, and visual details that didn’t make it into the film. You eventually came to agree that these minor characters and storylines weren’t really necessary to the main story. But was it difficult to let go of how you had envisioned some of the scenes being filmed? For example, at the sectional game, you described the gym as being “alive with 16 different cheering sections, 16 different sets of colors.” And as the team bus drives to the state finals, you described the bus passing first farms and small towns, and then larger towns and cities, finally arriving in Indianapolis with its tall buildings.

You have to balance objectivity and subjectivity. You try to stand outside yourself and your own vision of what you want and be open to others. But you can’t be too open, because you get too many voices in your ear. It’s a fine balance between collaboration and having a singular vision. You can’t give away decision-making power. As a filmmaker, you have to let people know that you know exactly what you want, but you’re open to better ideas.

There’s always small losses. The biggest issue for me wasn’t what got left out of the script. It was cutting those 30 minutes [of deleted scenes] out of the movie. Our 2-hour-and-27-minute movie, I thought, was a hell of a cut. Of the deleted scenes, I always think there was a purpose for every one of them.

The thing that bothers me most about the movie, I still wince when Gene Hackman kisses Barbara Hershey. It feels unearned; it doesn’t feel natural. There were two scenes that built to that moment. If they hadn’t been deleted, the relationship would have evolved naturally.

What issues concerned you the most as filming began?

I had so many worries, because we hadn’t done this before. I didn’t have a tremendous sense of confidence. I struggled to imagine how we would get all of it done. I was daunted by the basketball. I didn’t have any anxiety about the actors.

During production, you believed the movie wasn’t turning out well.

The one thing that’s consistent about anything that’s creative, whether it’s writing or making a film, you just don’t know, when you’re in the middle of it, how it’s turning out. Moment to moment you can have a vision of success, insofar as, that turned out as I hoped, or better than I hoped. But you don’t know whether all those small victories will turn into something that cuts together.

The thing about making movies is, they’re never easy. They’re always hard. They’re just hard in different ways. Everybody who gets involved in the film business learns very fast how extraordinarily difficult and relentless and hard and consuming it is. And when you go on a movie shoot, it’s survival. We were under no illusion that this would be a walk in the park. But what Hoosiers has accrued in its afterlife has more than made up for any pain we went through during that two months of shooting. And people have a tendency to forget the pain anyway.

At what point did you realize that the finished film was actually quite good?

The first time I knew that we had something that people really liked was at our first [test] screening, in Irvine, California. We scored the highest test score in Orion’s history. The only time you really know [if your movie is good] is when your movie’s in a theater with an audience with no vested interest. You can’t tell when you’re screening for your friends or family or the studio. They all have their own tastes and bring their own biases.

Making your first motion picture was the fulfillment of a longtime goal for both you and director David Anspaugh. Most people realize that achieving a goal will involve hard work, determination, and sacrifice. But I think there may also be a tendency to fantasize that living your dream will mean reaching a state of ideal happiness and satisfaction.

I don’t think of it that way, as living my dream. We got an opportunity to make a movie we thought could be really special. We knew it would be really hard. The dream is the experience. The dream is the opportunity.

You should put your dream into context. Why is it there? What real meaning does it have? Whenever you achieve a dream, it does come at a cost. You are forced to create a new dream. And that’s not always easy.

I think a lot of people think, if I achieve my dream, my life will be different, I’ll be happier, I’ll be fulfilled. But it never happens that way. Hoosiers was my first script, and I’m working on my 29th right now. It’s not easier. Every script is just as hard as the last one. But it’s what I do. And it gives me fulfillment. Dorothy Parker’s line perfectly sums up my life and my work: “There’s nothing in this world that I hate more than writing. And there’s nothing I love more in this world than having written.”

“If it’s so hard,” people have said, “why do you still do it?” I do it because I would feel unfulfilled. I would not feel satisfied. I would not be fully maximizing who I am, and what I do, and what I think I can do well.

By the late 1980s, you were already talking about wanting to distance yourself from Hoosiers. But today it’s clear that you’re proud of the film and appreciate how much the fans enjoy it.

I think my reaction to the success of Hoosiers and Rudy, 10 or 15 years afterwards, talking to me about Hoosiers was like coming up to the great high school quarterback and asking him about that state championship game where he threw three touchdowns. To me, it happened a long time ago, and I’m not really interested in talking about it anymore. I’m focused on the things I’m doing now, my day-to-day challenges.

I accept how things have worked out. I’m grateful that the movies have sustained the way they have. And I accept it and embrace it.

In the years after Hoosiers came out, you were inundated with offers to write more sports screenplays. Initially you feared becoming pigeonholed as the sports-movie guy. But eventually you came to accept this direction for your career.

I knew so many people, and so many writers, especially, when I worked as an executive, who had a big hit or two or three, and barely any of them are still in the business. So I’ve had an opportunity to make a good living. I have a life that works. In the film business, everything’s so ephemeral. It’s sort of rare that anyone has sustained a career like I have. You don’t see too many writers who have major production credits that are 35 years apart.

I knew so many people, and so many writers, especially, when I worked as an executive, who had a big hit or two or three, and barely any of them are still in the business. So I’ve had an opportunity to make a good living. I have a life that works. In the film business, everything’s so ephemeral. It’s sort of rare that anyone has sustained a career like I have. You don’t see too many writers who have major production credits that are 35 years apart.

I still get [offered] variations on Hoosiers and Rudy; everybody has their own Rudy story. But roughly 1 out of 10 offers are really good, and maybe a few of them are great.

I had the opportunity, because of those movies, to write, to me, the best script I’ve ever written, about my boyhood hero, Mickey Mantle. I got to meet him and spend a lot of time with him and his family. It’s afforded me things that I normally would not have been able to even dream about.

I’m grateful for the fact that I still get hired, and I still get offers, and I still get to make really good money based on those two movies I made 32 and 25 years ago. I have a tremendous amount of gratitude.

Interview with director David Anspaugh

July 23, 2016

Did you employ a particular strategy or approach when directing Hoosiers?

One of my overall objectives was to keep it honest and keep it real in every area. And [to take things] just one hour at a time, one day at a time. I couldn’t look too far ahead. I just focused on getting the work done. My strategy was to stay healthy and take it one day at a time. And to stay true to the spirit of the script that Angelo [Pizzo] wrote.

How would you describe your directing style?

I have a reputation of being an actors’ director, and I’m very proud of that, because that’s my juice, that’s the kick I get out of what I do, more than anything else—working with an actor to get a performance that neither one of us could have imagined. My heroes were Elia Kazan and Woody Allen and John Cassavetes and John Huston. Most of the directors I’ve admired or who were really inspiring to me were actors at one time.

Before filming began, did you work with the three main actors on developing their characters? Or did you give Gene Hackman, Barbara Hershey, and Dennis Hopper the freedom to create their characters on their own?

Angelo and I spent a great deal of time with Gene, starting at page 1 and going through every single scene, even scenes he wasn’t in. We wanted his opinion and feedback. And he’s such a smart actor, and his instincts are so good. And this was the first time Angelo had worked with an actor who, instead of wanting more lines, wanted fewer. With certain scenes, Gene would say, “I don’t need to say all that; I can act that.” So I thought it would be a magnificent experience, but it turned out to be pretty rough. But his work was flawless. With somebody like Gene, you kind of sit back and let him go. Look, if I thought he was just not getting the character or was heading down the wrong path, I certainly would have tried to get him to change course. But from the moment he opened his mouth, and when we did a read-through, Angelo and I looked at each other and knew we had stumbled into the best choice we could have made. And I learned a lot from him. So it wasn’t all horrible. I incorporated stuff I learned from him into my directing. Occasionally he would come to me or Angelo with a question. But he was always so dead-on right. The differences in the takes were so subtle.

Barbara came in a little early to talk to a lot of people and to try to get sort of the rural, Midwestern, middle Indiana dialect. She did a lot of work in that area. I didn’t really have to do much. She totally understood the character. She didn’t really have many notes in terms of how her character was written.

She ended up hating me and Angelo because so much of her stuff was cut out of the film. It’s too bad, because she was wonderful. She thought the movie was about her and Gene, as most actors do; she’s not alone in that kind of thinking.

In Dennis’s case, he came in to meet us before I cast him, and after a 3-hour conversation, we offered him the part. We talked about his character for probably about 2 hours. And he obviously got it. He’s the perfect actor to work with, because not only are his abilities so spectacular, he’ll dig his heels in with his point of view, if he has one. We would knock heads, but there was no ego involved. We were always trying to make it better. Every time, we would always come up with something better. A lot of actors don’t realize how stressful and ridiculously difficult it is to direct. Dennis had that respect for me and Angelo.

How did Hopper let you know he was unhappy with the scene in the original script in which Shooter leaves rehab in order to attend the state-finals game?

We sat down over coffee, and he said, “Guys, I wish I had brought this up earlier. I knew there was something that bothered me about this scene. It doesn’t work. It can’t happen. It would suggest Shooter didn’t take his sobriety seriously. And I know from experience that Shooter made a real commitment, and there’s no way he would leave that hospital.” And Angelo and I had been living with that scene in our heads for years. And we really argued against [cutting] it. And Dennis said, “No, trust me.” And we trusted him, and he was absolutely right.

What did you think of Barbara Hershey’s acting?

I was actually very happy with her performance. It’s too bad that most people never got to see the whole movie as it was intended, so that the relationship made much more sense. She’s a very good actress, and I thought she was cast beautifully. I was the one that fought for her, actually. She was not a terribly likeable character. But her character didn’t have a chance to really fully develop.

Did you help the Huskers develop their characters?

Angelo wrote so little dialog for Jimmy Chitwood because he knew the best basketball player probably would not be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. I knew I could help [the Huskers], but with the short amount of time that I had, I could not turn them into actors. But it all went back to the casting process. I knew I couldn’t take these local kids who had never had any acting experience and put them in a motion picture with Dennis Hopper and Gene Hackman and Barbara Hershey and not look like they were just completely out of their league. As we whittled down to our finalists, I tried to get to know each one of them—Angelo and I both did. And we really put them under a microscope. I wanted to find guys whose personalities were close to the characters Angelo wrote so that all they had to do was be themselves. But [being yourself is] the most difficult thing for anyone to do. But the basketball helped a lot. Because they had a task to do that kind of took their attention away from the “acting” part of it. And they really instinctively got their characters. And the more they spent time together, lived together, ate together, they became a real band of brothers. I was surprised. I thought it would be much, much more difficult. But Angelo kept the kids’ dialog to pretty much a minimum because he knew I would end up casting most of the movie out of Indiana with kids that had never acted before.

Did you believe that the lives of whomever you chose to play the Huskers would be forever changed because of the movie?

Before we offered each of those guys a part, we explained to them that, if we were lucky, and we made as good of a film as we hoped we could, it could be life-changing. We didn’t want them to feel they had been misled into something unpleasant or nerve-wracking. So we gave them examples of what they might be getting into.

Most movies don’t have seven or eight guys who’ve never acted before. Just the guts it took for these kids to be in a movie, having no idea what’s in store for them. Bless their hearts for having the courage to jump in headfirst with no real fear.

Was Angelo a steady, calming influence during the most difficult days of filming?

Yes. Going into battle together, we were always watching each other’s backs. When things would get really stressful and tough, and I felt like caving, or even giving up at one point, he was right there to throw cold water on me and give me a good slap in the face. His presence was invaluable. I don’t know what I would have done without him on that set. When things got really difficult with the schedule, the pressure was so intense, dealing with Gene on a bad day, I always had someone I could walk off with and go release some of that tension and get it off my chest. He was my sounding board.

Angelo has said it was important to him to have someone he trusted direct Hoosiers. He didn’t want some random director to be assigned.

He knew I understood what he wrote, that I understood it as if I had written it myself. He wanted to protect that. There was an opportunity for him to leave me at the curb. After we pitched the movie to Columbia Studios, privately they said [to Angelo], if you’re willing to get rid of Anspaugh, we’ll make the movie. And Angelo said no way. They also thought the movie might work better as a contemporary movie, where the coach comes into the inner city, so that it’s more relatable to kids today.

When the movie premiered, were you eager to learn what nationally prominent movie critics such as Siskel and Ebert thought about it?

If you try to make a movie for the critics, you’re screwed. You have to make it for yourself. You have to believe in it yourself. You bare your ass to the world, and they’ll either kiss it or kick it or both. But never believe the best reviews or the worst, because the truth usually lies somewhere in between. We knew it wasn’t a perfect movie, so we were prepared to get murdered [in the reviews]. We’d had enough good response early; the preview scores were high. We just hoped that the “major” critics, the A-list critics, would not jump all over it.

What would you like your legacy to be?

What would you like your legacy to be?

It’s really easy. There’s a sign in my bedroom that was given to me by both my daughters. It’s carved into an old piece of wood. And it says “Best Dad.” And that would be the legacy that I would like to leave. Because that, above all, is the most important thing to me.

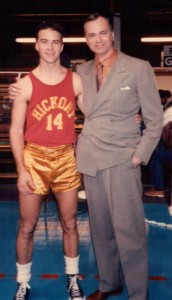

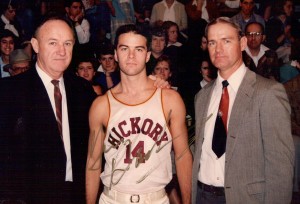

Interview with David Neidorf, who played Hickory Husker Everett Flatch

May 20, 2016

David Neidorf was a 22-year-old aspiring actor from Los Angeles when he was cast as Everett Flatch, Shooter’s son. Of the eight Huskers, he was the only one who was not from Indiana.

Tell me about your audition.

I am kind of athletic. I did not play basketball in high school. But I had started playing basketball in a local park near my apartment about eight months or a year before. I could run and shoot and look like I knew what I was doing. I had a basic sort of form; I didn’t have a modern approach.

It was at the Beverly Hills Y. The only guy I remember was Rob Lowe’s little brother, Chad Lowe, and he couldn’t play ball. They had us run up and down and scrimmage, 5-on-5. And some guys were trying too hard to be the star of the show. [The producers] made me feel good about what I did in that audition. You kind of get a sense of whether you’re in the running right away. You can almost tell as soon as you walk in the door, because that’s when the audition starts. They look at you, and they’re looking to see, is that who we think the character is? You can pretty much tell by that first look they give you if you have a shot.

Did it concern you that the other Huskers had no acting experience?

No. I was just totally happy to have a job. I was equal to them. And they were all really nice, and we hit it off. I was just trying to fit in. I didn’t want to seem like an arrogant jerk.

What were the first few days of production like?

The very first day I ever went to the set, I did not have to work, and I said, I just want to go out and see what they’re doing. And it was the scene where Fern [Persons] is with Barbara Hershey, and they’re throwing a sack of something in the back of a pickup truck. And I was like a kid in a candy store, amazed, watching all this. That was the first time I’d walked onto a movie set.

How did you go about developing your character?

I wanted to absorb the feelings around me, from meeting the other guys, who were really from Indiana, and I wasn’t. And the movie was set in a rural place, and I didn’t grow up like that. So I was trying to absorb as much from the people around me, and the lifestyle that I saw, to incorporate that into someone who had been abandoned by his father and was lonely and embarrassed in a very small community where everyone knows that about you, and that’s the first thing they think about you.

Was it intimidating dealing with Gene Hackman?

Yeah. Gene tried to be helpful, but it’s not in his nature. He’s a grumpy curmudgeon. He’s an incredible actor; the guy’s a genius. He held an acting class for all of us. I think he was just afraid that we were all gonna suck so bad. After that [class], nothing. He was not friendly to us.

As things went along, we all got more confident. We felt that whatever he threw our way, we could handle it.

Describe Hackman’s way of working.

He would intentionally not learn his dialog until 15 minutes before he had to shoot it so that he would have some sense of excitement that he would totally screw up. And being as good of a pro as he was, he never screwed up. Like that big speech in the locker room—he memorized it 15 minutes before he did it. He works from a highly agitated place.

I don’t think he accepted direction from David [Anspaugh]. One time he looked at David and he goes, “Are you even watching me?” Meaning, “Are you paying attention? I need someone to pay attention. Not that I need you to tell me what to do, but I need to know you’re paying attention.” And that was a pretty profound confession for this guy who’s won an Academy Award to say to a novice director.

Unlike Hackman, Dennis Hopper was not intimidating?

He never made you feel like that. He hung out with us a few times. One time we went to a bar. That was something Gene would’ve never done.

Working with Dennis was much easier than working with Gene. He was just more giving, not quite as self-involved.

Before you filmed a scene with Hopper, did you discuss it with him?

No, that’s not really how it works. When you’re working with an established actor, it’s more slanted toward what they want and need. It had nothing to do with rehearsing it, or talking about it, or thinking about the scene. It was more, I was gonna help him memorize his lines. I never talked with Dennis. We never talked about anything. I definitely never talked with Gene. They’re more focused on what they’re doing. It’s sort of a collaboration between unequals.

Tell me about the filming of the sectional game, with its fight scene.

That was Dennis’s first day of filming; we had never really met him. Right before the shot where he staggers onto the court, I went up to him and said, “I’m your son.”

The fight scene was expertly choreographed. It took us half a day to do it. The glass case had movie glass, so it doesn’t cut you. It kind of stings a little bit, because it doesn’t shatter, but somehow gets into little bits. I think we did it three times. I ruined one of the takes. It was in super slow motion, and the camera caught me saying f— as I was crashing into the case. I had to hit that thing in the right way, so that my head wouldn’t smash into the frame of it, which was real wood. I think it was fun for all of us. Boys getting to crash and break things—what could be more fun than that when you’re 22?

What do you remember about the hospital scene?

I was nervous. I knew it was a big scene, and I wanted my emotion to be authentic. So I was by myself, trying to work myself up into a frenzy for an hour or two. And I really cried on that first take.

Tell me about the diner scene.

It was a day-for-night scene, meaning it was night when we were shooting it, and they lit up the outside to make it look like day on film. And it was cold, and we were tired. I remember Gene complimented me after the scene was done, saying, “That was good; it was really simple.”

What can you recall about the scene in the locker room after the first home game?

There was an ad lib [at the end]. Steve Hollar told someone to shut up. And I was mad at him that day, and I said, “No, you shut up.” [Laughs.] And that was real; that was not in the script.

How aware were you of the difficulties caused by a couple of the lead actors?

We were pretty much shielded from it. It was all our first movie. And even though I was a so-called actor, I was in pretty much the same boat as the other guys; I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. So it was all fun to us.

I think Barbara felt marginalized. She hated Gene. He was really insecure about his love interest, because she was so much younger than he was. The kiss was really horrible. He was really insecure about that, didn’t like it, didn’t want to do it. [Hershey’s] bad attitude came from her bad relationship with Gene and from not necessarily feeling supported enough by an inexperienced director who could maybe recognize that and help her through that.

How would you describe Anspaugh’s directorial style?

David could be a little hyper or distracted. He didn’t exude the calm confidence that a veteran has. [But I give] a hat tip to David. He does deserve a ton of credit for being able to juggle all those things. [He could] handle enormous stresses.

What did you think of the movie when it was released?

I thought it was a little too sentimental. I never thought it would endure. I’m still not exactly sure why [it does].

It’s weird when you make a movie, because when you see it, you’re not just swept up in the illusion, but you remember, oh yeah, when that happened, there was this guy standing off camera, and he did this, or that was the day when so-and-so was mad. So you don’t see it with the same illusion that you see someone else’s work.

Interview with Eric Gilliom, who played J. June

May 4, 2016

Eric Gilliom, who grew up in Hawaii, was a recent graduate of the Goodman School of Drama at DePaul University in Chicago when he was cast as J. June, a player on the Terhune team, Hickory’s sectional opponent. Terhune, J. June, and J. June’s father were part of a subplot that ended up being mostly deleted during the editing process.

Tell me about your audition.

I graduated in 1985 and then I moved out to L.A. and got a manager and got signed with the Gersh Agency, and [Hoosiers] was the first audition they sent me out on. David Anspaugh and Angelo Pizzo were there, and the casting director, and people from Hemdale Productions. They liked my read, and they said, “Could you be at the Beverly Hills YMCA tomorrow?” A bunch of the people they were considering showed up at the YMCA, and we played a 5-on-5 scrimmage game. The other actors weren’t very good basketball players at all. I felt confident, because I could play basketball, and the movie’s about basketball. I think David Neidorf and I were the only two people that were chosen at that audition. I thought it was pretty awesome that the very first movie I auditioned for, I got. I was really excited to get the part.

Were all of you auditioning for the part of Everett, Shooter’s son?

I actually read a bunch of roles. I read the Jimmy Chitwood part. I didn’t know [they had cast me in] the J. June part until I left to fly to Indiana.

What was it like when you arrived for the filming?

The first time [all the basketball players] got together, we were staying at the Ramada Inn. The first time we met Gene Hackman, some of the guys didn’t really know who he was. But they knew who Lex Luthor was. But I knew everything about Gene Hackman. So I was kind of starstruck. He was really sweet. He was a really nice guy, very approachable.

I knew how huge basketball was in Indiana, but it was amazing to me—I was a nobody, but we had groupies. We would come out of our hotel, and there would be these groupies that wanted our autograph and wanted to hang out with us. [The filming] was a big deal for the whole state, I think.

What do you remember about the sectional game filming?

It was cold. It was really early in the morning. We had to leave at about 4:30 or 5 o’clock to get there. We did the basketball first. We ran up and down the court. Then we did some very specific plays. We’d rehearse it a couple times and then shoot it.

We had to play in the style of 1952. It took a while to get used to the set shot. You just don’t naturally play that way. They kept trying to get me to not do a jump shot. That took a little getting used to.

Was the staging of the fight scene complicated and time-consuming?

I remember it going pretty smoothly. They kind of did it in bite sizes.

The scene where Shooter stumbles into the game drunk was the first scene Dennis Hopper filmed in the movie. He had just recently arrived in Indiana.

For all of us, that was the first moment we ever saw him, and he came in in character. He wasn’t like an actor standing off-camera. He showed up in character. He was really nice too. For me, it was like, “Oh my God, you were in Easy Rider!” And the other guys were like, “What’s Easy Rider?”

Your other scene as J. June took place at the gas station / general store in Terhune.

I remember being so intimidated that day. I’m like, “Oh my God, I’m in a scene with Gene Hackman!” I was so nervous.

I had a much bigger role originally. My character was more involved in the plot. I was the rival on the Terhune team, and my character was established in the very beginning of the movie. Gene Hackman pulled into the gas station and saw me shooting hoops, making about ten shots in a row. When he found out I played for Terhune, he realized I could be a problem down the home stretch. When I played against Hickory [in the sectional], the fight scene had a lot more weight to it because of the setup that happened previously.

Before you saw the movie for the first time, did anyone warn you that your gas station scene had been cut? It ended up being reduced to only a couple seconds during the opening credits.

No. That was a shocker. My whole family came to the screening. It was an exciting moment. I was like, “I’m in the very beginning of the movie, Mom!” And the scene came and went. And my aunt leaned over and looked at me and she goes, “That’s it?” And I go, “No, no, there’s more. There’s supposed to be more!”

Interview with costume designer Jane Anderson

April 15, 2016

The basketball uniforms for all the teams were custom-made by athletic wear manufacturer Kajee, Inc. in Franklin.

Yes, Kajee was invaluable. The fabric, original to the time period, had limited yardage. Franklin was within reasonable driving distance of most of the [filming] locations. As I recall, the fabric arrived late [from New York state] for a comfortable lead time to manufacturing. At times we were picking up the uniforms and taking them to the set right before filming. Kajee came though with flying colors, and the uniforms were on set in time for camera. A grateful time.

The uniforms are some of the only bright colors seen in the movie. The everyday clothes and much of the scenery are drab.

The teams’ different colors were important for the storytelling, for school identification, and for the visual aesthetic. The colors gave energy to the games.

Were all the cheerleader uniforms custom-made as well?

Yes. A company in Los Angeles loomed the sweaters and manufactured the skirts. As I recall, the letter jackets were manufactured by another company.

How did you acquire all the necessary 1950s-style athletic shoes for all the teams?

We sent Converse the script, and they sent us all the shoes we needed.

You also needed to find saddle shoes for the girls.

We found the shoes in retail stores, but this required a lot of research. Lots of calls. We did not have the luxury of the Internet.

Were any of the main actors’ everyday clothes custom-made?

No. The bulk of the clothes were shipped from Los Angeles. They were rented from Paramount Studios and what used to be the Burbank Studios (now Warner Bros.). Gene Hackman was fitted in L.A. at Paramount Studios. Barbara Hershey and Dennis Hopper were fitted in Indiana the day after they arrived. All the clothes were from the late ’40s and early ’50s, without exception.

What kind of research did you do before creating the everyday clothes?

Massive research. I studied yearbooks, farm publications, newspapers, and photos, especially family photos. I made a massive call-out to anyone I knew who was in or from Indiana. But the yearbooks were the gold standard. I think I had about 35. I developed a research bible that I shared with [director] David [Anspaugh], [writer/producer] Angelo [Pizzo], and [production designer] David Nichols. I referenced the years 1948 to 1951, because most people’s closets contain styles from the past three years along with the current year. I referenced basic trends with the Sears fall and winter catalogs for the mentioned years. I found clothes that were a close match to what was in the catalogs, if not the exact match.

Interview with cinematographer Fred Murphy

January 31, 2016

Before you worked on Hoosiers, had you ever been to Indiana?

I’d never done a film in the Midwest.

Did you know anything about basketball?

I played when I was a kid, but I wasn’t a high school basketball player. I’d say I was relatively unknowledgeable about basketball.

Is it hard to work on a film when you’re unfamiliar with its topic?

It’s a good challenge.

What was preproduction like?

I had at least four to five weeks of prep. You read the script, talk it through with [director] David [Anspaugh] and [writer/producer] Angelo [Pizzo], start getting ideas about how you want it to look, and then you start going out and looking at locations, and eventually you do some kind of tests. Mostly it’s talking. And you also talk it through with the production designer. He’s also an important character in all this.

How did you collaborate with David?

David tells me what he wants out of a scene, we talk about how to do it, how to cover it, we look at various angles, he shows me his ideas, I show him mine. Usually well ahead of time you talk through what you want it to look like. And then you work your way toward how you’ll break down scenes. And David says I wanna do cuts, I wanna do one long shot. And then we’ll go to the place and figure out how to do that shot, where the camera should be, how we’ll light it, how we’ll shoot it. We worked out the basketball plays on a court ahead of time. We staged scenes with stand-in players to figure out how we were gonna shoot it, so we could walk around the court with a viewfinder to figure out where to place the camera.

Was working with a first-time feature-film director challenging?

I like working with first-time directors. They don’t have a lot of preconceptions, and they’re bursting with ideas and things they want to do. They’re so enthusiastic.

Tell me about the filming of the basketball games.

We did something interesting in that a lot of the basketball is broken down into almost scenes, as opposed to just sort of covering it, watching people run around and make shots. This wasn’t done that much [in earlier sports films], but we used a Steadicam and put the camera on the court, and it was actually cut like a scene. So you actually saw it like a small scene in motion. Unlike the way sports movies are often done, this was like a series of continuous scenes. [A typical sports movie] might have one important play, but often it’s photographed from a distance, and there’ll be some close-ups, but it’s not like a continuous scene where something is evolving and happening that’s emotional. Somebody steals the ball, somebody blocks, you see the other guy’s face, you see our characters, our team’s faces. You’re in there amongst them, and you really see it.

One great scene occurs during the first home game—the long tracking shot from the locker room stairs, through the door to the gym, and onto the playing floor.

You really feel like you’re on the court with them. With the Steadicam, you’re moving inside the court, with the players, as opposed to being on the sidelines, watching them.

What was it like filming in the cramped locker room beneath the Hickory gym?

It was very difficult. There were only a couple possible shots. There was one pipe that kept getting into shot that we couldn’t get out. [The room] had kind of a claustrophobic feel. The simplicity of it made you feel that this wasn’t a well-to-do high school. In the end, I thought [the room] really served us well.

Although it was filmed in a rush at the end of the day, the locker room scene at the conclusion of the first home game turned out great.

One of the virtues of this movie is that scenes are often played out in one shot or just a few shots. Or often things are played out in groups; there’s not a lot of cutting to individuals. And somehow all those shots work and have a strong sense of time and drama. They unfold at their own correct pace, without cutting to speed things up.

It rained a lot during production.

We were really lucky with the weather. With one exception, the sun’s never shining in the movie. It’s always gray and cloudy, sometimes misty and foggy, and rainy. Near the very end of the movie, there’s a brief shot of a cornfield, and the sun’s coming out. When we were shooting the scene in the church, it had been raining, and Oliver Wood, the DP of the second unit, wanted to go shoot the cornfield across the street because the sun was coming out. It’s one of the few times in the entire movie when we saw the sun. But the whole movie has that wonderful sort of gray, misty, foggy, slightly damp atmosphere, which I think really helped it. It felt like fall into winter.

We were really lucky with the weather. With one exception, the sun’s never shining in the movie. It’s always gray and cloudy, sometimes misty and foggy, and rainy. Near the very end of the movie, there’s a brief shot of a cornfield, and the sun’s coming out. When we were shooting the scene in the church, it had been raining, and Oliver Wood, the DP of the second unit, wanted to go shoot the cornfield across the street because the sun was coming out. It’s one of the few times in the entire movie when we saw the sun. But the whole movie has that wonderful sort of gray, misty, foggy, slightly damp atmosphere, which I think really helped it. It felt like fall into winter.

Did you communicate with the film’s editor during production?

Mostly it was David who would do that. I talked to the editor only once in a while. What I would do is call the [film developing] laboratory every morning from the pay phone in some gymnasium. I had a handful of quarters. I’d call my friend at the laboratory for 5 minutes to see how the film had turned out, the color, how’s the exposure, as it came off the machine.

You watched the dailies at the end of each day.

We put together a screening room—I guess it was at the hotel. We stayed in this crummy motel on the outskirts of town. [The crew] filled this entire motel.

What else do you recall about the filming?

The most difficult thing I remember is the noise when we did scenes in the gyms—just the noise of having all those people there, because they wouldn’t keep quiet, no matter what. The noise was, after a while, unbearable. That was the lone thing that drove me crazy—the talking of hundreds and hundreds of people.

Several scenes that were in the original screenplay didn’t make it into the movie, because there wasn’t enough time to film them all. Also, because the distributor wanted the movie to be no more than two hours long, some scenes that were filmed ended up on the cutting room floor.

As I recall, the first cut of the movie was very long—3 and a half hours. The film editor did a very good job. Especially with montage-ing a lot of basketball games. That actually propelled the story in a terrific way that wouldn’t have happened if we had shown all the basketball games. With people writing their first screenplay, it’s often the case [that they write too many scenes]. Part of it is passion—wanting to get everything in the story. The one hard thing about movies is trying to tell a story in 2 hours. That seems like a long time, but it’s not.

Interview with Bill Chestnut, a member of the Oolitic team

January 15, 2016

Bill Chestnut was a senior at DePauw University when he heard about the open casting call to find basketball players for the movie. He had played basketball at Cloverdale High School. He ended up being cast as #15 on the Oolitic team in Hickory’s season-opening game.

My high school coach told me about the tryouts to be in Hoosiers. I went to the gym at IUPUI, I ran up and down the floor about five times, they said OK, and I walked out. I thought that was it, but then someone called to me from down the corridor, wanting my contact information. A month or so later, I went back and read from the script. They asked if I was willing to be an extra, and I said sure. Acting wasn’t really my thing.

I went for an afternoon practice at Brownsburg a couple weeks before the game filming that would take place at Knightstown. I showed up at the Knightstown gym early on a Wednesday morning to film. I was given a uniform, warm-ups, and a country-boy outfit, which I tried to give back. The lady told me I would need it for the afternoon, because our game filming would be done by noon, and I would need to be in the stands for the next game. I decided not to argue; I would just leave the clothes after filming the basketball game.

At 7 p.m. (11 hours later), they asked if we could come back in the morning to finish filming the game. I spent the night at Butler University in Indianapolis with one of my high school teammates who was a student and basketball player there. I returned to Knightstown in the early morning for another full day of filming, only to be asked to return on Friday. This created problems for a few of my Oolitic teammates; they could not return because of college commitments. I called my professors that evening. They agreed to let me take tests the next week.

We did negotiate our salaries. Those who could come back would be paid the normal rate of $3.50 per hour until noon on Friday. According to our contracts, that was when we would be done filming. Any hours past noon that we continued filming would be double time. I spent another night at Butler after buying a change of clothes. We started again by 8 a.m. on Friday, and I believe we finished about 10 or 11 p.m. Luckily Steve Hollar was making his shots, or it would have been later. They did honor their verbal contract for $7 an hour from noon until 11.

The first day was interesting and fun. After that it was monotonous and long. The overall experience was great.

When I saw the movie and actually saw myself on the screen, it was neat. When the movie was deemed a classic, I realized I was the player who is fouled when Coach Dale refuses to put Rade back in the game. That helps keep my little part significant: I’m the player at the free-throw line when Coach Dale decides to play with just four Huskers.

Having big “small-school dreams” for my hometown during my youth keeps this movie very special.

Interview with Todd Baxter, a member of the Cedar Knob team

January 16, 2015

Todd Baxter was a junior at Indiana University when, one day in November 1985, he saw a flyer posted in the theater department saying that extras were needed for the filming of a movie.

I’m not even sure it said what the movie was. I called up, and they said it was a movie about basketball, and I said, “I’m only 5-7,” and they said, “That’s OK; it’s set in the ’50s; you don’t have to be very tall,” and I go, “Well, I don’t really play basketball,” and they go, “You’re an extra; it’s fine.” I didn’t have a car. They said, “You’ll have to make your way up to Indianapolis.” So I borrowed my roommate’s car to drive up there a couple days later.

Todd was cast as a bench-sitter on the Cedar Knob team.

How specific were the director’s instructions for the fight scene?

We weren’t told where to stand. I kept thinking if I stood next to the coach of our team, I’d be seen, but actually I ended up not in the right spot to be seen. Because I’m so short, it didn’t really help much. They didn’t tell us what to do [during the fight]. It was more pushing and shoving, really.

We weren’t told where to stand. I kept thinking if I stood next to the coach of our team, I’d be seen, but actually I ended up not in the right spot to be seen. Because I’m so short, it didn’t really help much. They didn’t tell us what to do [during the fight]. It was more pushing and shoving, really.

At the time of filming, no one knew how popular Hoosiers would become. Most of the background actors simply thought it would be fun to appear in a movie, and that’s why they did it.

I got paid a little. I seem to remember it was something like $100. It was a fun thing to do. The money was kind of an extra.

Do you remember the first time you saw the movie?

I don’t remember the first time I saw it. When I saw it with people, they wouldn’t have seen me, because [my scene] happened so quickly. It happened so fast that I couldn’t say to somebody, “Look! There I am!” It was only years later, when you got VHS, that you could pause it. But even with VHS it was never clear enough to go, “See? That’s me.” It was only when you got DVDs that you could stop it and they would go, “Oh, yeah, that is you.” The other thing that didn’t help was they cut my hair so short, because it was the ’50s. My hair was usually long and fairly curly. And they put wax and stuff in it. So people would look at [that scene] and go, “That’s not you.”

Six years after the filming, Todd moved overseas for work. Today he lives in London.

[My friend Jeff] and I were talking about [the movie] a couple years ago on Facebook, and he goes, “That’s my favorite sports film ever,” and I was kind of taken aback, partly because I still kind of thought of it as that small little movie. So I was kind of surprised when he said it was rated as the top sports film. … For Indiana, [the mid-’80s] was kind of a unique time. Hoosiers was released the same year as the book A Season on the Brink, about the IU Hoosiers, which was the year before my last year at Indiana, which was 1987, when they won the NCAA [men’s basketball tournament]. There was just so much Indiana basketball around that time. I think the film benefited from the IU Hoosiers winning the NCAA.

Do you still have your Cedar Knob warmup jacket?

I do. I don’t know how that ended up in my bag!

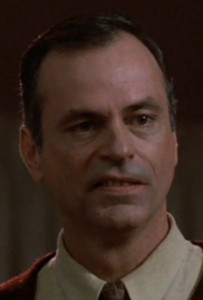

Interview with Chelcie Ross, who played George Walker

August 26, 2014

Your character, George, hopes to see Norman fail and be fired as coach. Did you view George as a bad guy—the villain of the movie?

George was not a bad guy, nor was he a villain. I certainly never thought of him in those terms. Cinematically he did serve as the antagonist until opposing teams took over that role.

George had an ego. He had been a good high school basketball player and no doubt thought he was capable of coaching the team. Instead, he was humiliated in front of the team, and, in a town that small, that meant everyone in Hickory knew all about it.

In the scene where George is leading the first basketball practice, and then Norman abruptly dismisses him, do you think Norman is too harsh with him? Or does George need to be put in his place because he has overstepped his authority?

George told the coach in their meeting in the barbershop that he, George, knew exactly how the team should be coached and that Norman should pay attention and maybe take some notes. Again in the gym, George told Coach Dale what the plan was and how he was going to do it. It was imperative that the coach take control, make a statement, and let there be no question as to who was in charge.

Your character is the father of Buddy, one of the Huskers (although this fact isn’t mentioned in the film). Do you wish that you could have had some scenes that showed you being a father, instead of mainly being someone who opposes the coach?

I cannot explain why my relationship with Buddy is never mentioned. As an actor I would like for that to have been explored, but that’s another story—one which really doesn’t get us where this tale needs to go. Its omission didn’t hurt the film a bit.

Director David Anspaugh and writer/producer Angelo Pizzo have talked about how stressful the filming was. It was their first movie. They felt the pressure of dealing with a short schedule and a small budget. And Gene Hackman and Barbara Hershey were difficult to work with. Was the friendship between Anspaugh and Pizzo instrumental in helping them get through difficult days? And how would you describe the general atmosphere on the set?

Those of us in the larger roles who were on the set from beginning to end were aware of the tension between David and Angelo and their stars. Nonetheless, the atmosphere on the set on a day-to-day basis was mostly upbeat, positive, and productive. There were the occasional meltdowns and boilovers. There always are. David and Angelo were fortunate to have each other and their long friendship to keep each other upright and headed in the right direction.

I had very few dealings with Barbara Hershey. We said hello, exchanged pleasantries, and sat in the stands together. That’s all. So I really can’t speak to that at all.

Several years after Hoosiers I worked with Mr. Hackman again on The Package. The director, Andrew Davis, encountered the same tension, the same head-on mano a mano working relationship that David had dealt with. They both experienced tears and frustration at times and great success for their efforts.

I will not pretend to analyze or explain Gene Hackman. He is one of the best film actors ever, and I learned more from him than from anyone else I have ever worked with. He was very generous with me from day one. The “Leave the ball, George”/“two kinds of crazy” scene was my first day and my first scene. Needless to say, I was all nerves, the new guy jumping right in with the screen legend. I had no need to be nervous. Gene, he said to call him, was generous and complimentary and treated me as if we were equals, peers. I have not forgotten it, and I have tried to treat every actor I have worked with in the same way.

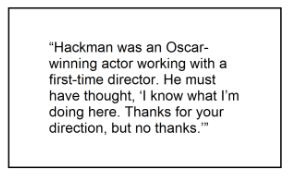

I do think there are two obvious things at work here. First, Hackman was an Oscar-winning actor working with a first-time director. He must have thought, “I know what I’m doing here. Thanks for your direction, but no thanks.” Secondly, David was the default authority figure. Gene, like Norman, wanted to make it clear who was in charge of Gene.

Seven of the eight Huskers had no acting experience. How well do you feel they handled their roles, along with the pressure of being in a movie?

The boys on the team were wonderful. Trained actors with some basketball experience could never have done as well. They became a team and friends and thoroughly enjoyed themselves. I don’t think you can overstate the contribution that their shared history as Indiana boys and Indiana basketball players brought to the film. You can’t fake that.

Yes, they were insecure about the acting, but it did not take long to get past that. I played high school football and well remember being so nervous before games that I felt I would lose my lunch any minute. Then came the first hit, and when I got up off the ground, the nerves were all gone. I think once the guys got that first hit behind them, they knew they could do this.

Do you remember the first time you watched either a rough cut or the final version of Hoosiers? What were your initial impressions of the finished product?

I don’t specifically remember the first time I saw it. I know I loved it immediately except for some nitpicking and the guy who played George.

What’s your favorite scene in the movie?

My favorite scene is Ollie’s underhand free throws. When I played high school basketball in New Jersey (before the industrial revolution), we had guys who shot them that way.

Is your role in Hoosiers one that fans remember and recognize you from the most?

No. I am recognized every day as Eddie Harris in Major League. Then Hoosiers and Rudy are about equal. Also, fans of Mad Men recognize me as Conrad Hilton. Beyond that the recognition factor depends a lot on what was on TV last night.

You’ve been in quite a few movies. Sometimes, even when the production had problems and many things seemed to go wrong, a motion picture can still turn out great. Why do you think this is?

To date I have been in fifty-seven movies, and many of them have been in danger of not getting finished at some point in the process. They all did, with varying degrees of success. There is a lot of money at stake. Moviemaking is the world’s biggest team sport. Look at the crawl (credits) at the end of any film. The success of the project depends to some extent on each of those specialists doing their job well. And, of course, everyone knows that the biggest egos in the universe are involved. It’s a miracle any film ever gets finished.

In my experience, My Best Friend’s Wedding, The Long Walk Home, Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey, A Simple Plan, and Richie Rich all hit some very rough weather, and some were close to sinking. They made it mostly because they started with a great story, a good script, and strong people committed to making sure the story got told.

Interview with Spyridon “Strats” Stratigos, Hoosiers technical advisor and referee in the Lyons game

August 24, 2013

You befriended Hoosiers director David Anspaugh and screenwriter/producer Angelo Pizzo when the three of you attended Indiana University in the late 1960s. At the time, Anspaugh was making 16mm films. What were they like?

You befriended Hoosiers director David Anspaugh and screenwriter/producer Angelo Pizzo when the three of you attended Indiana University in the late 1960s. At the time, Anspaugh was making 16mm films. What were they like?

They were kind of silly; they were shorts. They were probably more like music videos than movies. In retrospect, I don’t mean to demean David, because I thought what he was doing was extraordinary, but to look back at them, I don’t think they necessarily carried any kind of dramatic plot.

Also during this time, Anspaugh and Pizzo, who loved movies, began discussing ideas for what they thought would make a good film. Did you participate in these conversations?

We talked about movies all the time. We went to art films. There was a great little theater in Bloomington, the Von Lee, that was part of our cultural life. They had Truffaut films, Buñuel, Ingmar Bergman films, and also early American films, even early Hitchcock. It was a great place to cut your teeth on great films. … [Anspaugh and Pizzo] had a great deal of interest in film work, David more than any of us from a technical standpoint because he was taking photography courses at IU, and probably about the only film class that was offered at IU at the time. In 1969, Angelo and I were in Hawaii for the summer; we worked over there. And we went to a casting agent, and we were cast in an episode of Hawaii Five-0. We were to play beach bums who would be playing with a beach ball in the background. Later that year David and Angelo got involved as extras in the movie Winning, which titillated their fantasies even more in terms of doing something [in Hollywood]. But this was more of a David thing. Angelo at the time was more of an academic. Even when he went to film school, it was more to be a teacher of film history than to actually make movies.

Do you remember when you first heard that the production of Hoosiers would become a reality?

[After college] Angelo and I kept close through basketball; we talked about IU basketball all the time. And it was then that I first heard about doing a movie based on the Milan story. It just seemed so impossible at the time. … I remember their travails of trying to sell the screenplay, their meetings with different people, the time they went to Jack Nicholson’s house, showing him the script, their near misses, going to see Burt Reynolds about doing the lead role. They were trying to find a star that would attach himself to the film so they could sell it. I remember when they finally got the deal with Hemdale Productions—the joy and ecstasy with those guys. I mean, they were just knocked out that they were actually going to make this movie.

You were one of three technical advisors on the film. What were your duties?

I had just left academia and opened up a restaurant in ’84–’85. I didn’t play basketball at high levels. I was a high school player and played AAU basketball and played with a lot of good players. But I like to think that I’m a student of the game. They asked me to go up to Indianapolis and audition basketball players and meet the casting director and his assistant and work with them. [Technical advisor and former IU player] Tom Abernethy and I worked together and started having official practices [with the Huskers] because we wanted to form this kind of team concept. We’d meet in the gym; sometimes Gene Hackman would come by. But we wanted these guys to get to know each other and create an offense and a defense like we were a real team. [Technical advisor and high school coach] Tom McConnell was a consultant for that era; he knew that era. … After we cast all the [opposing] teams, we still had not cast the South Bend Central team. And I went by myself and auditioned that whole team; those were my guys. And I had to work with them too. We didn’t have a whole lot of time to work with them. We had to really work on our feet when we got to Hinkle [Fieldhouse], to set stuff up.

In the original script, the opposing state-finals team was Gary Roosevelt. In a later revision they were renamed South Bend Central, which is your alma mater.

Angelo did say in the South Bend Tribune that [the change] was an homage to me. That may be true or not. But if you weren’t gonna use Roosevelt, South Bend was the other major state power in the ’50s. South Bend Central won two [state crowns], and Attucks won two or three during the [Oscar] Robertson era, so Milan kinda slipped in there. And South Bend Central had the same kind of racial mix that [1954 state runners-up] Muncie [Central] did.

What was the open casting call to find the Huskers like?

Let me tell you, you can tell if a guy can play basketball in about 3 seconds—how he dribbles, how he shoots. We could eliminate most of those guys. A guy that’s never played basketball, you can’t fake it. This is the brilliance of Angelo and David: They wanted basketball players because it’s easier to train a basketball player to act than an actor to play basketball. And we wanted authenticity. … [Casting director] Ken [Carlson] looked at [Maris Valainis, aka Jimmy Chitwood] as a guy that had screen aura. He thought Maris had sex appeal. I had no clue about that, but I saw the guy was hitting jump shots.

One of your tasks was to help teach the Huskers to play 1950s-style basketball. But you played high school ball in the 1960s. Did you do some research?

I looked at film and I talked to coaches of that era. It was a very interesting time in the game, the early ’50s, because the game was developing. The jump shot, for example, was just coming into being. Bobby Plump had kind of a push jump shot. But you still had guys shooting push shots, where they lifted their leg up. If you notice, we have both in the film.

You also appeared as a referee in the Lyons game, where you had a speaking role. What was it like to be on camera?

You also appeared as a referee in the Lyons game, where you had a speaking role. What was it like to be on camera?

It was one of the greatest experiences of my life. It really was; it changed my life. I got to choose which referee part I wanted. The reason I chose that one was because there were actually two scenes [with that character]. The first one was cut; they never shot it. I never realized how much work was involved in shooting a simple scene. Actors have to hit their marks. I was having trouble hitting my mark; I kept going too far. And Dennis Hopper was sitting there, and he kept teasing me. But Hackman was not happy. Because one thing about Mr. Hackman, he’s a pro. And he never misses his mark. After about two or three takes, he was getting agitated. And Dennis was having fun with it. He was helping the production people put down bigger pieces of tape. Eventually my mark looked like an airport landing strip! After I was finished doing that scene with Mr. Hackman, he shook my hand and said, “Very good job.” Gloria Dorson [who played Cletus’s wife] introduced me to her agent, and I ended up having an avocational career as a professional actor. I eventually got into the Screen Actors’ Guild and then found a love for theater and did a lot of theater work over the last 25 years.

It was one of the greatest experiences of my life. It really was; it changed my life. I got to choose which referee part I wanted. The reason I chose that one was because there were actually two scenes [with that character]. The first one was cut; they never shot it. I never realized how much work was involved in shooting a simple scene. Actors have to hit their marks. I was having trouble hitting my mark; I kept going too far. And Dennis Hopper was sitting there, and he kept teasing me. But Hackman was not happy. Because one thing about Mr. Hackman, he’s a pro. And he never misses his mark. After about two or three takes, he was getting agitated. And Dennis was having fun with it. He was helping the production people put down bigger pieces of tape. Eventually my mark looked like an airport landing strip! After I was finished doing that scene with Mr. Hackman, he shook my hand and said, “Very good job.” Gloria Dorson [who played Cletus’s wife] introduced me to her agent, and I ended up having an avocational career as a professional actor. I eventually got into the Screen Actors’ Guild and then found a love for theater and did a lot of theater work over the last 25 years.

Being good friends with Anspaugh and Pizzo, and working behind the scenes, you were well aware of the difficulties they faced and their serious doubts about how the movie was turning out.

The drama that was going on behind the scenes was unbelievable. [Anspaugh] had a really hard time directing Gene Hackman. And David’s a sensitive guy. It was really difficult on him. And Angelo was being required to rewrite on the spot. The drama was intense!

Did you also feel the movie wasn’t turning out well?

I had no idea about that. … When I watched Dennis Hopper work, I thought, “Whoa, this is way over the top.” And then I’d see it on film and it was perfect. And in all fairness to Gene, I didn’t think he had a clue about how to coach basketball. I thought, “This is going to be awful; he looks like a fish out of water.” I see the film, and he’s brilliant! It’s like he’s been a coach all his life! So that tells you how much I know about what I was seeing and what was going to be the final result. One thing I did know, from watching the dailies, was that it was going to be beautiful, because [cinematographer] Fred Murphy shot some really nice stuff.

Anspaugh and Pizzo sometimes had disagreements but overall functioned effectively as a team. Why do you think they work well together?

I think they’re a wonderful combination. These guys have been best friends forever. They sometimes get on each other’s nerves, like friends do. I think they’re perfect complements to each other. David has the eye and the ability to work with actors, and Angelo has the wonderful gift to tell a story. And it’s a perfect blend, to have a writer and a director that are of the same mind and complement each other so well. I think it’s part of the magic of the film.

Considering all the behind-the-scenes drama, and the pressure the filmmakers felt because of the relatively short shooting schedule, and the fact that they didn’t feel confident about the film’s quality, why do you believe the finished product turned out to be as good as it is?

David, God, he’s really good. And I think he was underestimated by the actors, that he could pull this off. He’s got a wonderful eye; he’s a sensitive guy; I think he knows how to bring the best out of people. I think you’ve got to give a lot of credit for the movie’s success to not only Angelo for giving him the screenplay, but to David for making it work.

Why do you think Hoosiers has remained so popular over the years?

Obviously it touched a chord on a lot of levels. On the level of sports movies, so many coaches feel like they know the story. There’s the whole theme of redemption, the struggle with alcoholism. It certainly is a classic film. I remember Dennis Hopper, after seeing the dailies, he said, “You know, this thing has the look of a John Ford movie.” And he was right. They captured the period perfectly. There’s something timeless about the quality and the way they shot this. All the extras were real; they were all Hoosiers, which gave real authenticity to the film. And it’s the same story you’ve heard a million times; it’s the David and Goliath story. And that’s the thing it was criticized for, its predictability. But that’s not what it’s about; it’s about how you get there. The story was really about the journey. I think it affected some people on a sports level, some on a character level, some because it captured a time and place that doesn’t exist anymore—particularly in Indiana, where we’re so proud of that heritage.

Audio clip: Strats thinks one of the movie’s best qualities was the casting of real Hoosiers.

Audio clip: Strats recounts how he made Barbara Hershey laugh by acting foolish during a break in game filming.

Interview with Brad Long, who played Hickory Husker Buddy Walker

July 10, 2013

You played basketball in both high school and college. How good were your teams?

You played basketball in both high school and college. How good were your teams?

Probably the best team I had in high school [Center Grove in Greenwood] was my junior year. We were 16 and 7 that year, but we got upset in the sectional. [At Southwestern College in Winfield, Kansas] my senior year was probably our best team; we were 20 and 5.

How did you learn about the auditions to find the Hickory Huskers?

I read about it in the paper. I graduated [from college] in the spring of ’85, came back home. About May, June, they were having articles in the paper saying they were looking for players to portray this Hickory High School team. I had a lot of my friends encourage me, saying, “You ought to give it a shot.” And back then I looked young for my age. I was able at 23 to come off as a high school student.

The first round of auditions involved only playing basketball. What were you required to do in the following callbacks? Read from the script? Improvise? Talk about yourself?

We did a little bit of all of that. They wanted to see how well-spoken you were, could you speak in front of a camera. I don’t remember actually reading lines from the script. I think it was more just improvisational dialog. They looked at your basketball ability first. It’s almost like they put more emphasis on your basketball than they did your stage presence.

As you progressed through each round of callbacks, and the number of hopeful actors was narrowed down each time, did you begin to feel more confident that you would be offered a role?

It was almost a cautious optimism. You knew that there were a lot of guys trying out for the part. You almost felt like a needle in a haystack. Through the whole process, I just had fun with it. To me, it was like a big press conference, like we’d had in college. … [Eric Gilliom, cast as J. June, a Terhune player who originally had a small speaking role] read for Buddy; he was considered for the Buddy part. I was up for J. June and Buddy and happened to get Buddy. I got the better end of the deal!

Before filming began, the Huskers underwent some acting instruction with Gene Hackman. What kinds of exercises did he have you perform?

We did what I would call monologues; we’d make up a story. They wanted to see if you could produce emotion; we did what were called forced-emotion exercises. They would make you think of something that would make you very sad, and you’d try to cry. That was hard to do. But Gene was real easygoing about it. There wasn’t a lot of anxiety or nervousness with those monologues, because you felt like you were among friends. It was fun. I actually enjoyed doing it. We also had to pick our favorite song and start singing it. I’m an Eagles fan, and I started singing “Take It Easy.”

In the screenplay, the descriptions of the Huskers are minimal. Buddy is described as “George’s son, good looking, cocky, and a great ball handler.” Did the director encourage you and the other Huskers to think of ways to develop your characters and bring them to life?

When I read that [Buddy was cocky], I remember thinking, here’s my chance to do what I never did in high school or college—just kind of be a bad boy. They did give us a little bit of leeway. I’m a gum-chewer; I have been my whole life. They noticed me chewing gum a lot. The Dentyne line was a perfect setup. [Screenwriter/producer] Angelo [Pizzo] and [director] David [Anspaugh] had an idea of what they wanted—I wouldn’t say they strayed too much from their main ideas—but they were flexible on things. One example, the scene where I get kicked out of the gym [at the first practice], the script called for me to be surprised. But I think Gene talked to Angelo and David about this. They felt like I might be more angry than surprised, because Coach Dale had just kicked out my dad—George, the interim coach. So it made more sense for me to be mad. And I walk out and actually slap the door. That was improv; I did that on my own. And Angelo and David said, let’s leave it in.

The script mentions that George is your father, but this isn’t stated or shown in the movie.

As the season progresses, and we’re doing well, you see George sort of supporting the team, and Buddy also falls in line too. So it’s kind of like the dad and the son bought into the new system.

As the season progresses, and we’re doing well, you see George sort of supporting the team, and Buddy also falls in line too. So it’s kind of like the dad and the son bought into the new system.

The first basketball scenes to be filmed were the sectional game. This was more complicated to shoot than most of the other games, because it included a drunk Shooter wandering onto the court and later a fight. Were you nervous about having to shoot more-involved scenes first?

The other side of that might be, because we did kind of some heavy-lifting scenes early, it sort of made you realize, “If I can do that, I can do anything.” It might have been a confidence booster.

What did you and the other Huskers do on the days when you weren’t needed for filming?

We would hang around the hotel. We [also] were able to go home, back with our families. If we weren’t needed on set on a particular day, we might be given the day off, and we could go home. In retrospect, it was odd that I could go home and eat with my family and then film a scene the next day. Sometimes we would go watch the scenes being shot. As long as we weren’t in the way, we got to watch some of the scenes being shot, even when we weren’t needed on location.

The Huskers were housed at the Ramada Inn on the far westside of Indianapolis during the filming. Shown are Kent Poole and Wade Schenck.

Kent Poole and Steve Hollar visit with Laura Robling before the filming of one of her scenes in Liberty Chapel, site of principal Cletus Summers’ and Coach Dale’s homes.

Do you have a favorite moment or memory from the filming?

There’s so many. [My favorite scene was] the scene with Everett and Dennis [Hopper] in the hospital. That was really an emotional scene; it really felt real. You know, for me the best times were, as much fun as it was to film, off-camera things we got to do—play 3-on-3, or go to the craft service to get lunch. It was just a fun atmosphere. And just getting to know the guys—even the gaffers, the lighting people, the craft service people. You get to know those people; you become sort of a family. So, to me, that’s probably what I missed the most—those relationships you make and friends you make.

Were any of the scenes particularly difficult to shoot?

To me, the easy scenes to shoot were the basketball scenes. The tougher ones were the ones where you really had to concentrate on acting—because we were not actors, except for David Neidorf. We were just nobodies from Indiana who loved basketball. So whenever we got into the scenes where we really had to think about lines and what we were saying, those were tough, because we’d never done that before. I think of the scene I did with Gene, where I [tell him I want to] get back on the team. [It was cut from the film but appears in the collection of deleted scenes on the DVDs.] For about a four- or five-day period I really had to concentrate on what I was saying, how I was saying it, how it was perceived, my energy level, making sure it didn’t look like I knew where the camera was.

What aspect of the moviemaking process surprised you the most?

How much time it takes. I was just amazed at how much time goes into setting up a scene that might last 8 seconds. Like at Knightstown, they would get there at 3 in the morning—the lighting, gaffers, all those folks—and get the court ready, get the lighting just right, the shade. There was even a guy that walked around with smoke, to make things misty. There’s all kinds of tricks I didn’t know about. But they would be there hours before we were scheduled to shoot. And then the scene they set up might be a 12-second scene. I was just amazed at the time and effort and detail. They probably filmed enough footage for five movies. The “hurry up and wait” thing was kind of a surprise to me. Movies are fun, but they’re not all fun and glamour. There’s a lot of waiting around.

How much time it takes. I was just amazed at how much time goes into setting up a scene that might last 8 seconds. Like at Knightstown, they would get there at 3 in the morning—the lighting, gaffers, all those folks—and get the court ready, get the lighting just right, the shade. There was even a guy that walked around with smoke, to make things misty. There’s all kinds of tricks I didn’t know about. But they would be there hours before we were scheduled to shoot. And then the scene they set up might be a 12-second scene. I was just amazed at the time and effort and detail. They probably filmed enough footage for five movies. The “hurry up and wait” thing was kind of a surprise to me. Movies are fun, but they’re not all fun and glamour. There’s a lot of waiting around.

Your dad played the coach of the Linton team in the regional game. How did that come about?

Angelo approached me and said, “By any chance, is your dad Gary Long?” I said, “Yeah, he is my dad.” He said, “Did he play at IU back in the late ’50s, early ’60s?” I said, “Yes, he did.” He said, “I rebounded basketballs for your dad.” As a 10-year-old boy, Angelo would go to the old Fieldhouse and rebound for the IU basketball team [during practices]. He went on to say, “How would he like to be in the movie?”